Published on October 4, 2017

25 min read

Beyond CI/CD: GitLab's DevOps vision

How we're building GitLab into the complete DevOps toolchain.

With GitLab 10.0, we shipped Auto DevOps for the Community and Enterprise Editions. Read on for an in-depth look at our strategy behind it, and beyond.

I recently met with my colleagues Joe and Courtland to give them the lowdown on GitLab's DevOps vision: where we've come from and where we're headed. You can watch the video of our discussion or check out the lightly edited transcript below. You can also jump into the rabbit hole, starting with the meta issue for GitLab DevOps.

CI/CD: Where we've come from

When I joined GitLab about a year ago, I created a vision document for CI/CD, and outlined a lot of the key things that I thought were missing in CI/CD in general, and going beyond CD. I literally called one section "beyond CD" because I didn’t have a name for it then.

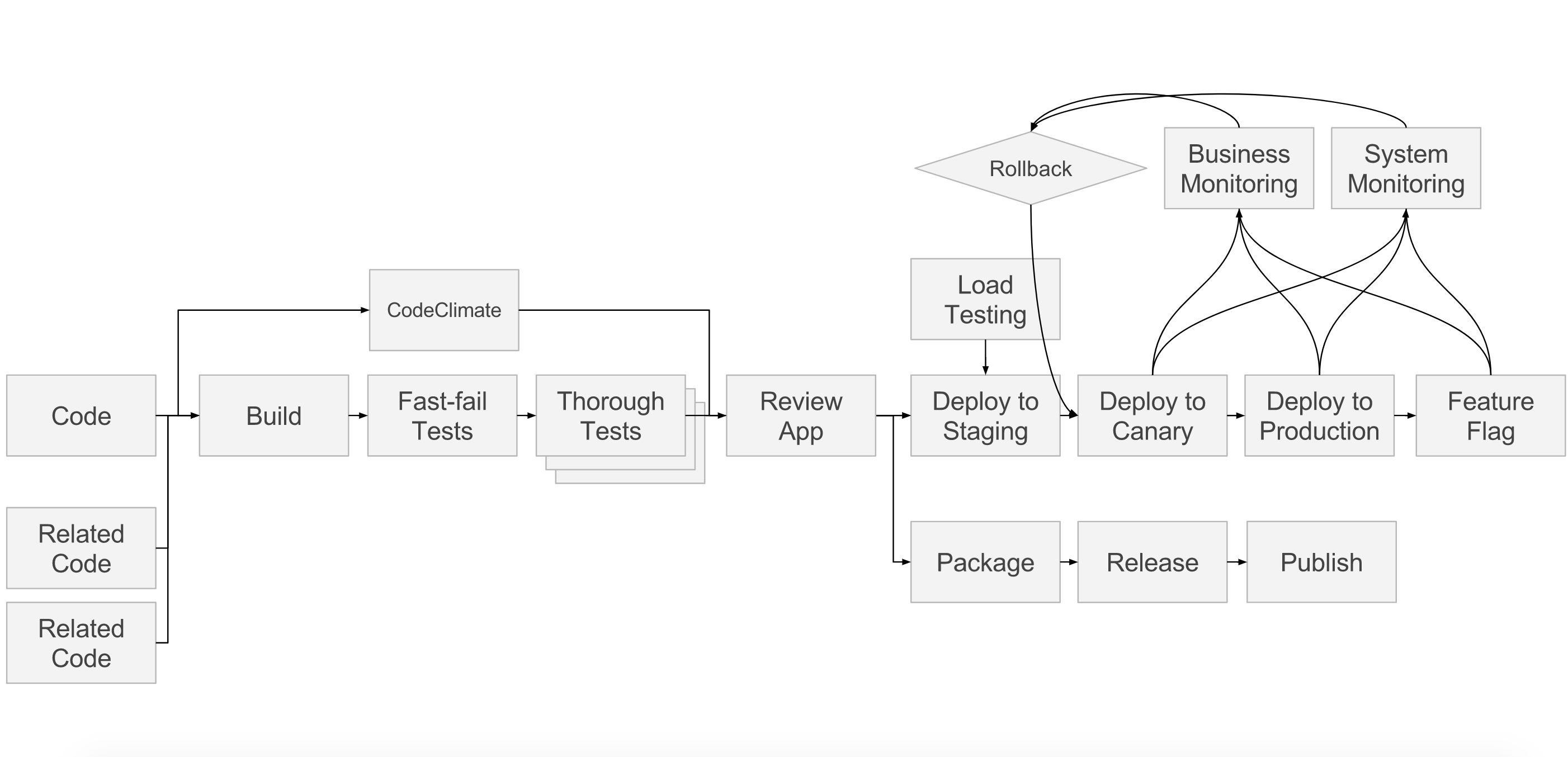

And in that document, I create an example pipeline to characterize all this stuff, to show how the pieces fit together into a development lifecycle.

I love this diagram not only because it's complex and scary, but because when we started, we had maybe four boxes filled in, and now we have 10 or 12 filled in. To start with, we had code management and, obviously, builds and tests. And we kind of did deployment, but not really.

Since then, we’ve added review apps – a specific example of deployments – which is really awesome. We also added a more formalized mechanism for doing deployments; actually recording deployments and deployment histories, keeping track of environments, and everything else. Then we added Canary Deployments in 9.2 and code quality in 9.3. We added system monitoring with Prometheus in 9.0.

We don’t yet have what I called "business monitoring," which could mean monitoring revenue, or clicks, or whatever you care about; but that’s coming. We don't yet have load testing, but the Prometheus team is thinking about that. We don't yet have a plan for feature flags, but I think it's a really important part.

And then we have this other dimension of pipelines, which is the relationship between different codebases (or projects), and in 9.3 we introduced the first version of multi-project pipelines.

So we've gone from a core view of three or four boxes to where 90 percent is complete. That's pretty awesome.

It became obvious to me that we were viewing the scope with this hard line: developer focused rather than an ops focused. For example, we’ll deploy into production, and we might even watch the metrics related to your code in production, but we’re not going to monitor your entire production app, because that’s operations, and that’s clearly out of scope, right?

Where we're headed: Beyond CD

What hit me a few months ago is, "Why is that out of scope? That’s ridiculous. No, we’re going to keep going. We're going to go past production into operations." Most of this still applies, but instead of just monitoring the system as it relates to a merge request, what about monitoring the system for network errors, outages, or dependency problems? What if we don't stop at production, and monitor things that are typically ops related that may not involve a developer at all?

Then I realized that this thing I called Beyond CD, maybe it's really DevOps. Maybe the whole thing is DevOps.

The DevOps tool chain

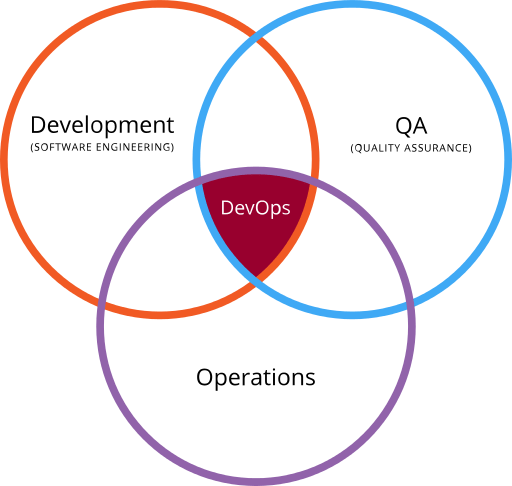

To offer some context: DevOps is hard to define, because everybody defines it slightly differently. Sometimes DevOps is defined as the intersection of development, operations, and quality assurance.

Image by Rajiv.Pant, derived from Devops.png:, CC BY 3.0

For the most part, my personal interest in DevOps has been in that intersection. We do great code management; we’ve done that for quite a while. How do we get that code into production? How do we get it into QA?

Review apps are a great example that fits squarely in that tiny, little triangle in the middle of the Venn diagram. You take your code, you deploy it, which is an operations thing, but you have it deployed in a temporary, ephemeral, app, just for QA people (or designers, product managers, or anyone who is not a primary coder), so they can test your application for quality assurance, feature assurance, or whatever.

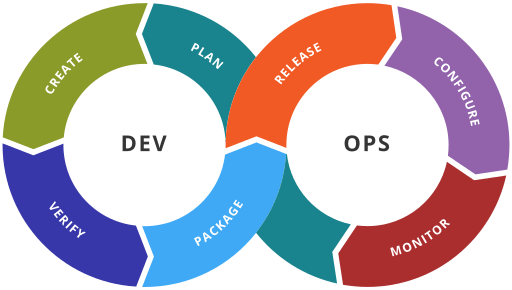

But now, I'm looking beyond the intersection. Here's the DevOps tool chain definition from Wikipedia:

Image by Kharnagy (Own work) CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Well, that’s everything! That’s not the intersection; that’s the union of everything from code, to releasing, to monitoring. And that's where things get confusing. Sometimes when people talk about DevOps, they’re not talking about all of your code stuff. It’s the intersection parts that are the interesting parts of DevOps. It’s the parts where we let developers get their code into production easily. That slice, that intersection, of the Venn diagram, that’s the interesting part about DevOps.

Having said that, as a product company, we are going to deliver things that are pretty squarely on the development side, and, eventually, we’re going to deliver things that are pretty squarely in the operations side. At some point, we may have an operations dashboard that lets you understand your dependencies in your network infrastructure, and your routers, and your whatever. That’s pretty far fetched at this point, but it could happen. Why not? Just have GitLab be your one operations dashboard, and then it’s not just about the intersection of the DevOps, it’s the whole DevOps tool chain.

So, that is the whirlwind, high-level summary of where we've been, and a little bit about where we’re going. Now let's get into specific issues.

The Ops Dashboard – #1788

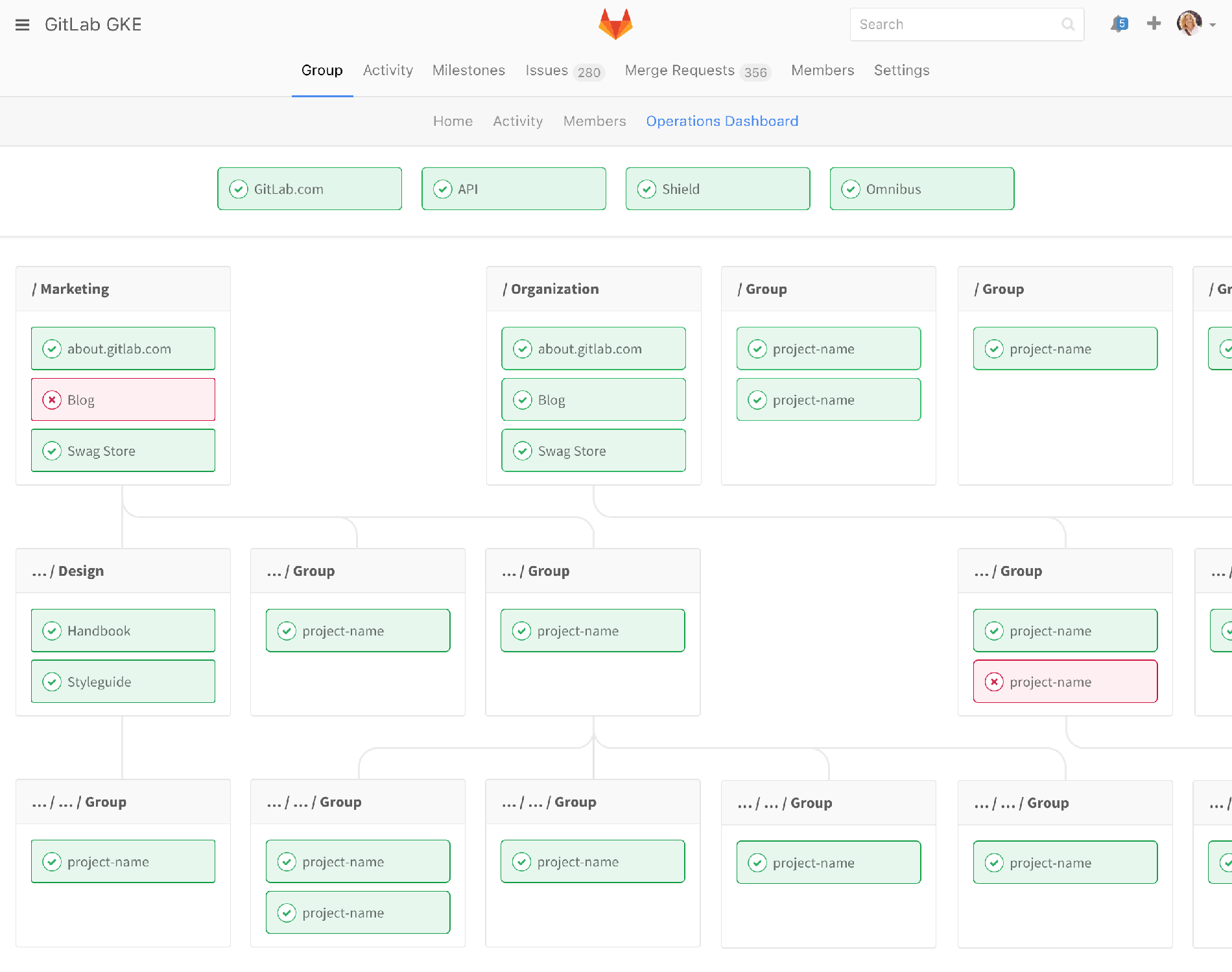

We have a monitoring dashboard that's very developer centric. What about taking that same content and slicing it from the operator's perspective? For a moment, ignore all the stuff below, let’s just pretend there’s only the four boxes at the top:

So an operator might want to know, "What’s the state of production?" If I'm a developer I can go into a project, into environments, see the production environment for that project, and I can see what the status is. But what if I want to see all production environments? As an operations person, I care a little less about individual projects than I care about "production." So this is giving me the overview of "production." All of these little boxes would represent production deploys of projects that you have in your GitLab infrastructure.

The view is explicitly convoluted because we had just introduced sub-groups and I wanted to make sure this mechanism expanded. So ignore all the stuff below and just look at the top-level dashboards. Or maybe one level down, which is already still pretty complicated, but let’s say your marketing organization had different properties than your other developer operations; you’d be able to see really quickly what the status is. If something’s red, you’d be able to click down, and see details.

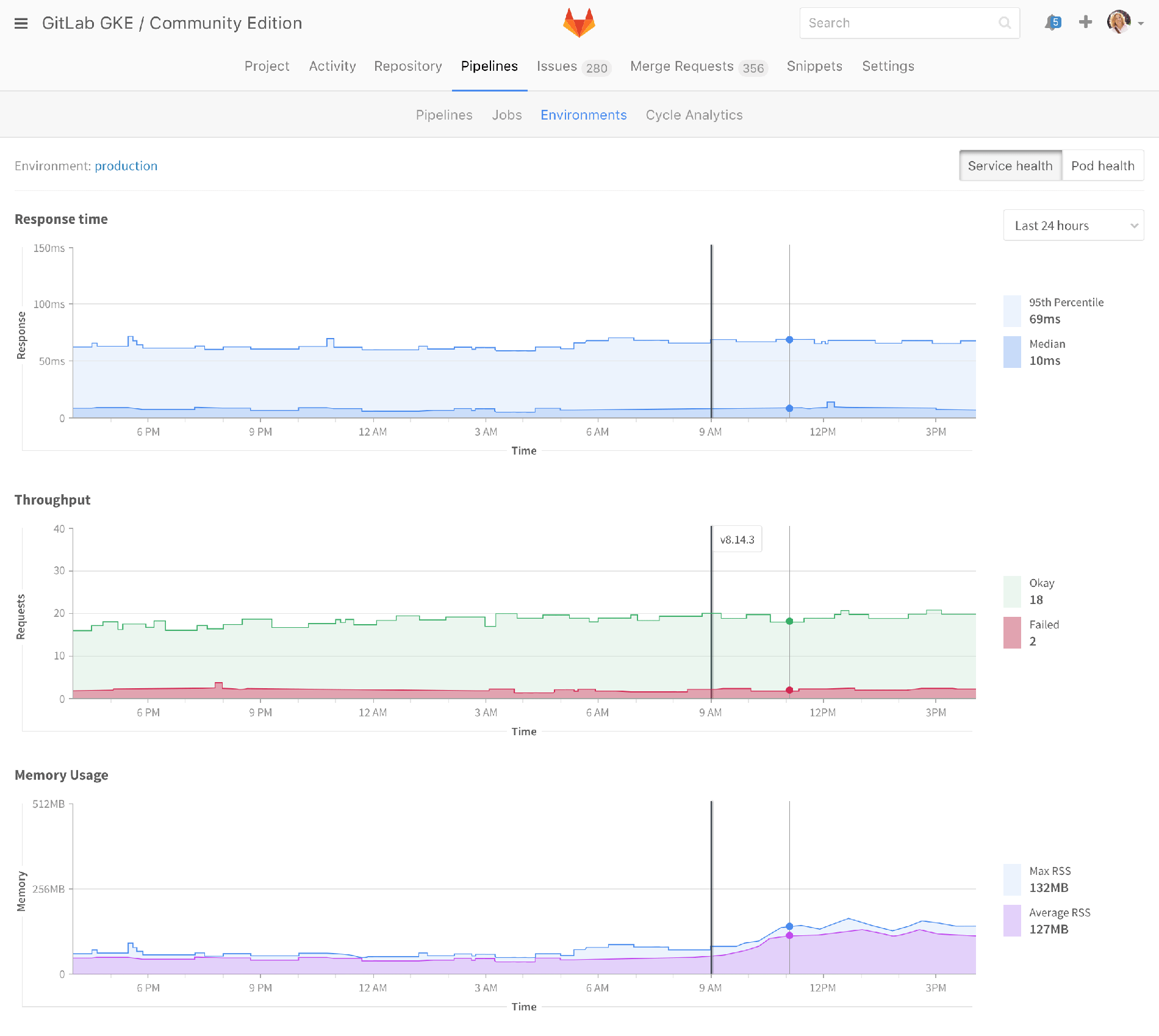

You’d be able to see graphs like this, which are similar to what we already provide, but from the other angle. As a developer I’m looking at the deploy, and saying, "Oh, how did my deploy affect my performance?" But this is saying, "How’s production? Is anything wrong with my entire production suite?"

This is really just scratching the surface of the ops views of things, but I think it's going to become much more important as people embrace DevOps. You want your developers to be talking the same language as your operations people. In a lot of organizations, it’s already the same people – there are no separate operations people. Developers push code to production, and they're paged if something goes wrong. In others, developers and operators are separate, but they want to work together towards DevOps.

Either way, you want to be using the same tools. You want to be able to point to, for example, a memory bump that your operations people should also be able to see. But if they’re using completely different tools, like New Relic and Datadog, that kind of sucks. So let’s give them the same tools.

Pipeline view of environments – #28698

I particularly love this proposal, and I really want to see this happen soon.

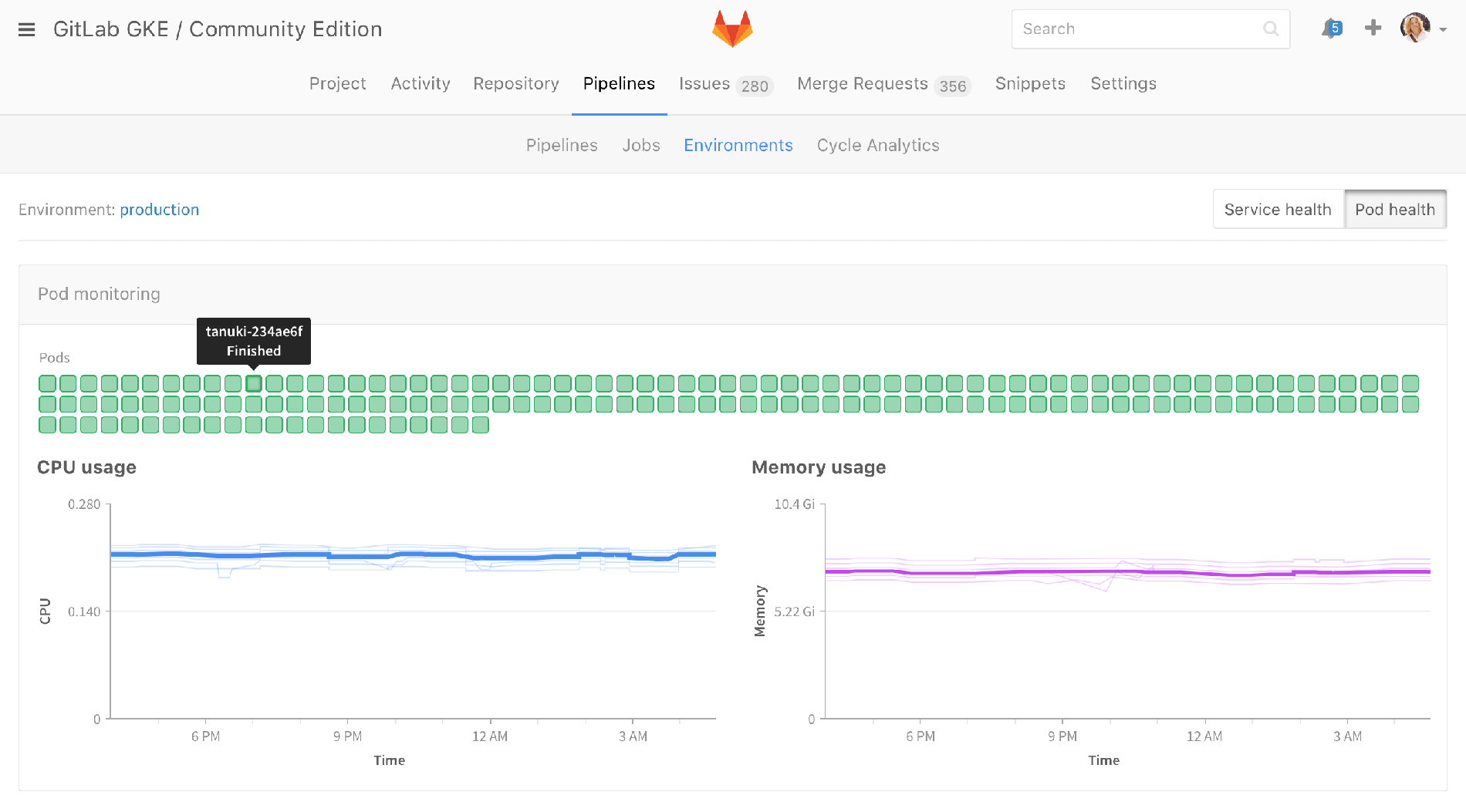

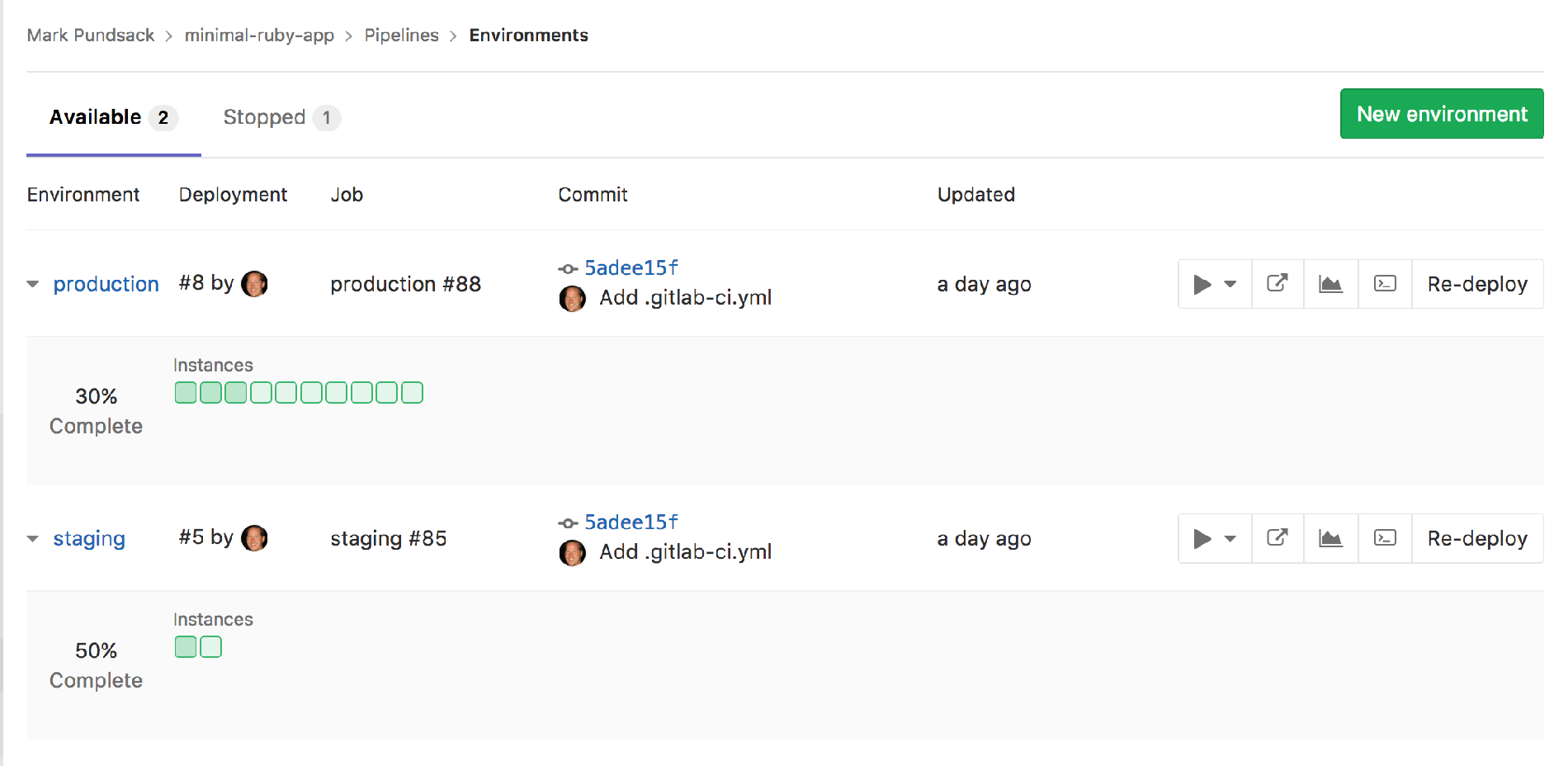

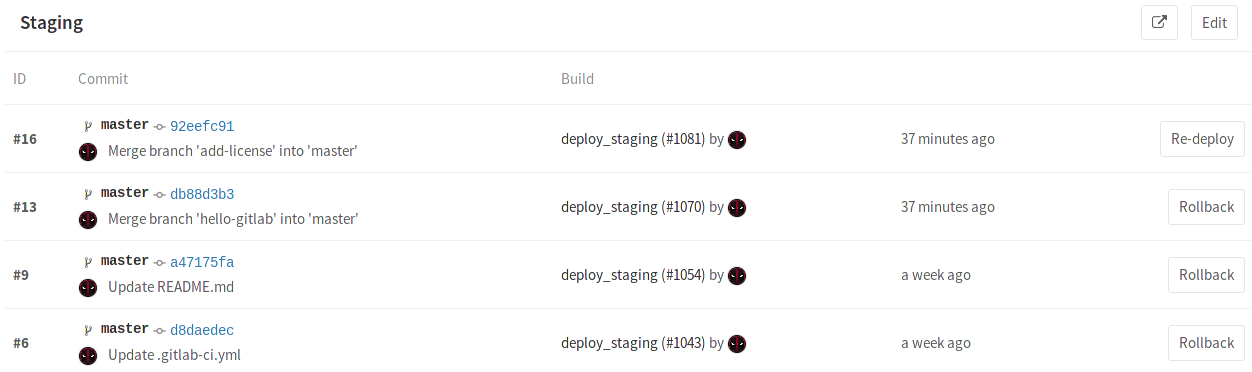

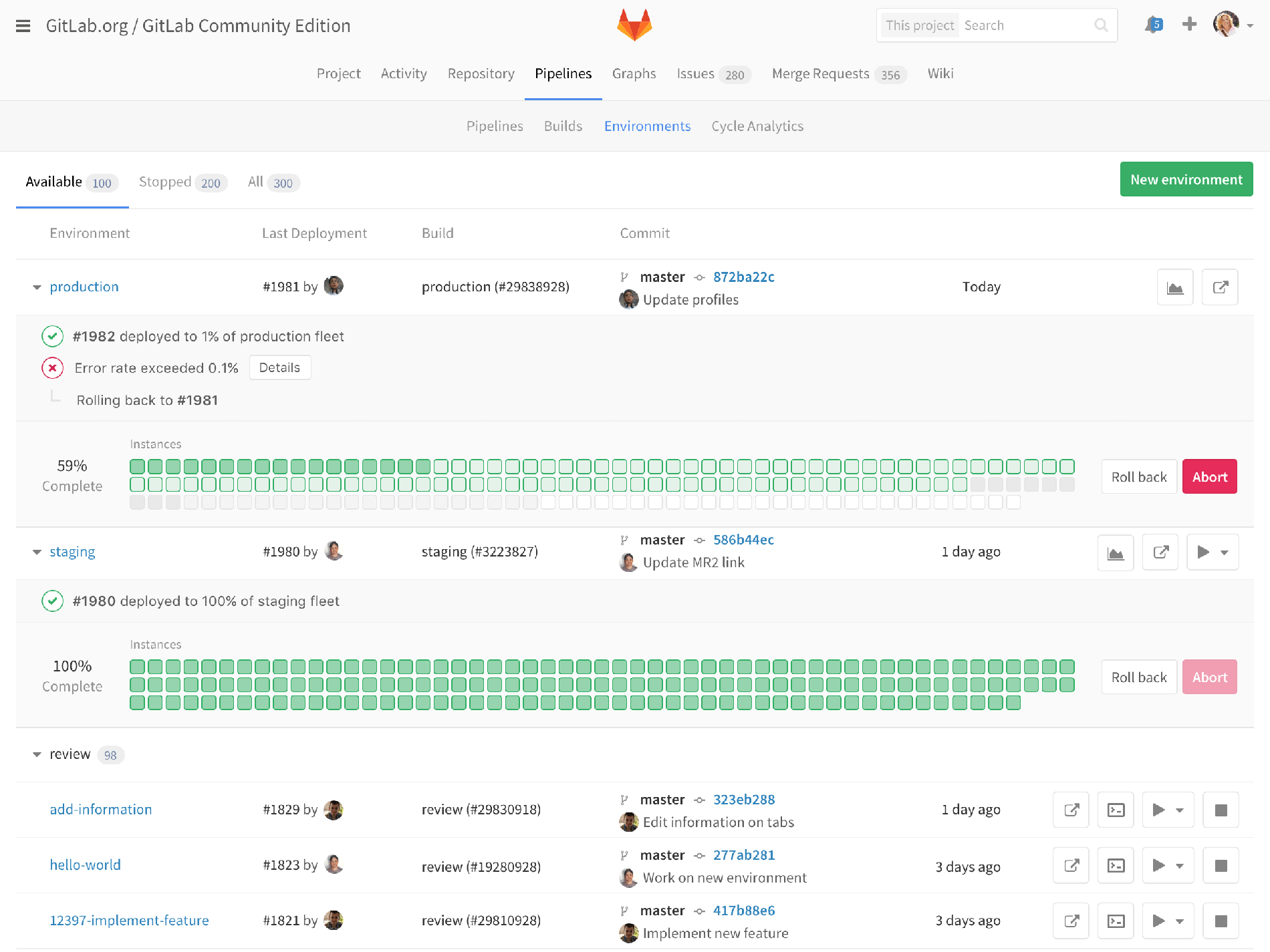

The environments page today is just a list of environments showing the last deployment. The picture tells you who deployed, which is good, and you can see that the commit is from the same SHA as staging, which is kind of nice. I can see the deploy board, and if there's a deploy ongoing, I’m able to see the state as it rolls out. We don’t yet show you the current health of these pods; once they're deployed, all we know is that they're deployed. This is how the environment view is today, and it's centered around deployments.

Current Environment view

Current Environment view

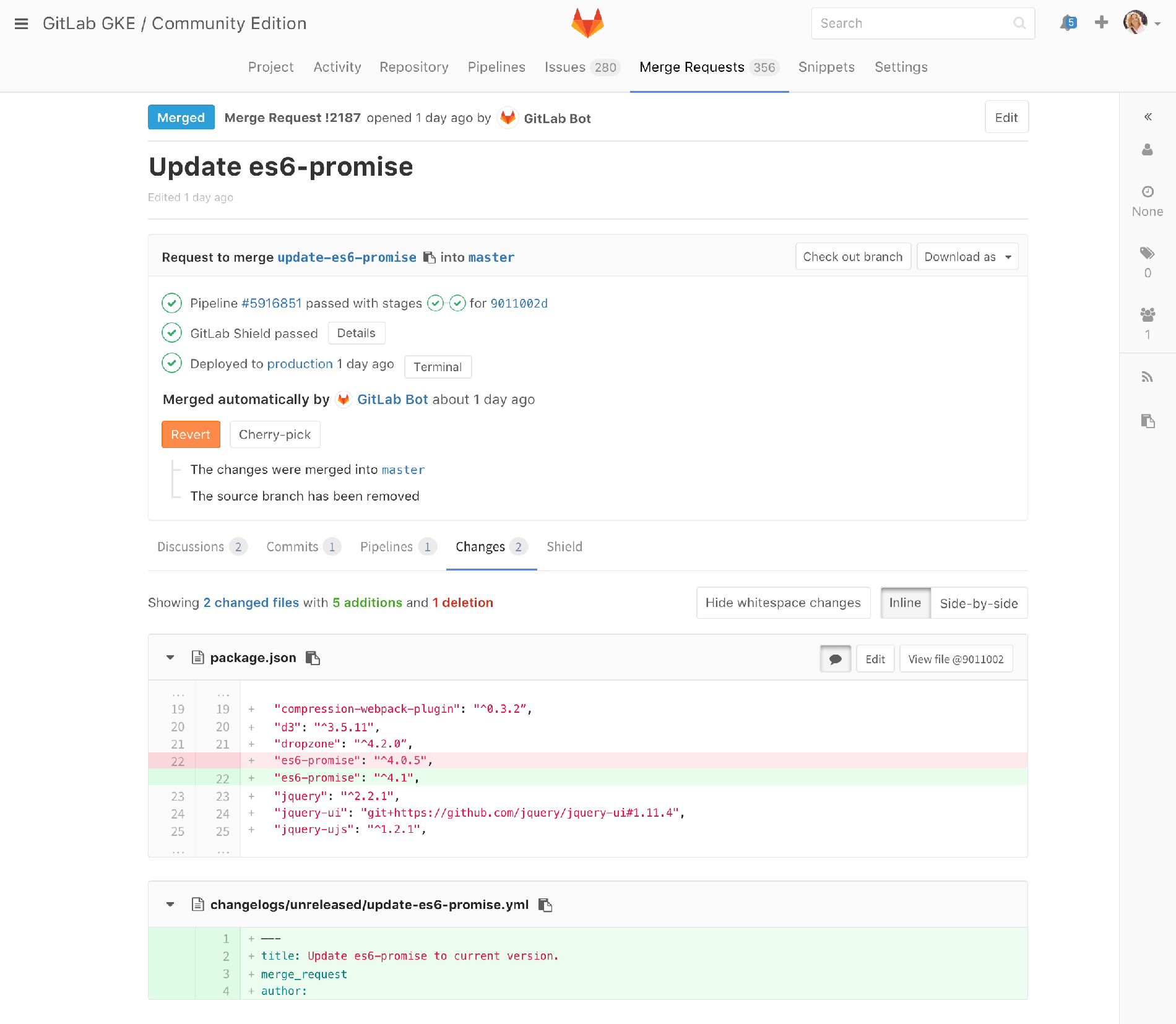

You can click through to see the deployment history and this is actually really valuable because I can see who deployed things, how long ago, and if something went wrong in production I can really quickly roll back and let the developers have some space to go and figure out what went wrong.

Current Deployment History view

Current Deployment History view

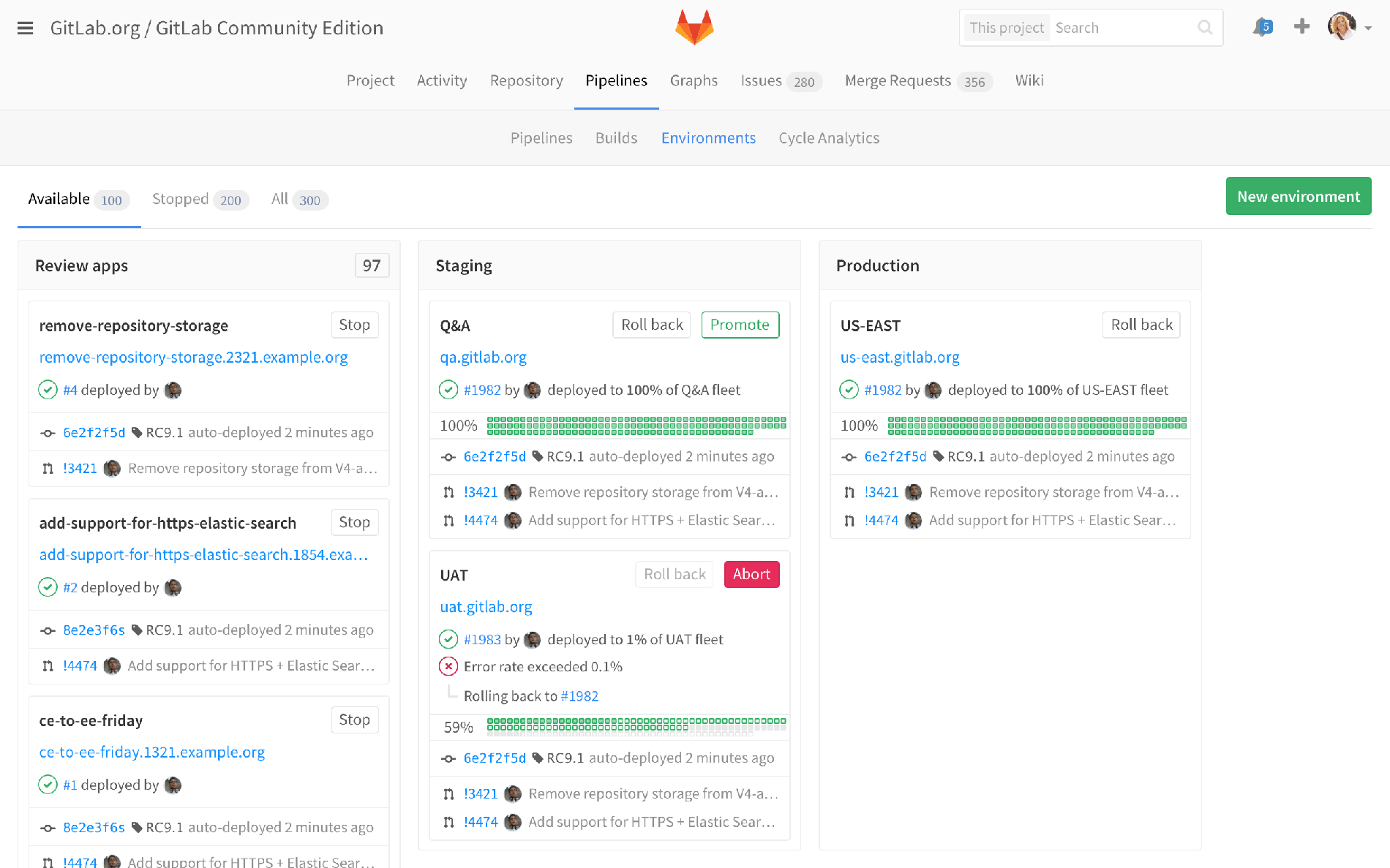

But this proposal turns it around to have more of a DevOps view of the thing.

Proposed pipeline view of Environments

Proposed pipeline view of Environments

The idea is to take the same application, and instead of just looking at a list of environments, I’d be looking at columns with lots of review apps, and some number of staging environments, and a production environment. Instead of just showing you the SHA, we would show you, for example, what merge requests have been merged into staging that are not yet in production. That’s a great marriage of these two views, that you’d be able to see the diff between them.

This list, although it’s just a mockup, shows maybe the last five things that were in production, or what was included in the last deploy, or whatever works best for your environment. Showing what’s in the last deploy might be enough, but for people who deploy 17 times a day, maybe that’s a little less useful, and we just show history.

But then what about building in more of the operations kind of stuff, and saying, "Alright, what’s the state of my pods?" Here we were flagging where the error rate exceeded a threshold and there’s some alert that popped up. And here we’re showing this automatic rollback kind of stuff, but basically just really building on this ops view. Of course this is still a DevOps view, in the sense that I’m looking at an individual project. So, one permutation of that would marry that ops view of all of production. Or if I’m looking at a microservices kind of thing, where there are five or 100 different projects, and I want to see the status of all those really quickly. See #28707.

Dependency security – #28566

So, here, the idea is that you've deployed something in production, and some module or something that you depend on has been updated, not by you, but by the community, or someone else.

The easiest and most naive way to approach this is that with the next merge request, or next CI/CD run, we would go and check to see if anything’s outdated. And we might fail your CI/CD because of this.

It would make much more sense to run this stuff automatically. Even if, for example, nobody pushes for seven days, and in the middle of that, there’s a security release; just proactively run stuff and notify me. So, that's sort of a second iteration of thinking about how you would notify somebody, and tell them, "Oh, you’ve got a security change. You should go in and do something about it."

Now, the third iteration is, "Well, what would you do with that information?" You’d go and maybe give it to your junior developer to go and make the change, and point to the new version. And then, of course, you need to test that it works. So, you’re going to create a merge request, and then test it, to make sure that it still functions properly.

Well, why notify somebody, and tell the junior developer to go and do this? Why don’t we just do it for you? Why don’t we just go and submit the merge request for you, and then tell you what the results are. And, in fact, let’s go further, and say, "Hey it passed. We just deployed into production for you." Why would you have security vulnerability in place any longer than necessary?

And instead of having 100 alerts about 100 projects or microservices that all need to get updated, you just get alerts about three of them that fail, that actually have some weird dependency that it didn’t work on. And then, you can focus on real problems.

So, that’s a glimpse at how we’re thinking about this.

This would definitely be an enterprise-level feature. And again, we've fleshed out some ideas and it’s unscheduled, but it does really tie into the ops mindset.

Question: Enterprise Edition features

Courtland: You mentioned that sort of automation would be an enterprise edition feature. Can you talk a little bit more about why a smaller development team, like under 100 developers, wouldn’t get value out of something like that?

Mark: So, this is where things get a little tricky, because of course, smaller developer teams would get value out of that too. Everybody would get value out of that. Some of it has to do with proportionality. One test I like to use is: is there some other way you could achieve the same thing, using workarounds, and we’re just making it easier? And that’s a good case, here. You can already do this, but we’re going to automate it. And automation is something that affects larger companies a lot more, because they’ve got hundreds of projects, with thousands of developers. And they just can’t deal with the scale, or it’s worth dealing with the automation. Whereas, if you’ve got a small developer, with a single project, you’re pretty much on top of it. And if something changes, yeah, you just go ahead and fix it; you’re aware of it. The bigger challenges are when you’re just not aware of how this thing might affect one project that somebody’s almost forgotten about.

The other thing is that, just to be blunt, our concept that Enterprise Edition is only for more than X people, is a little flawed. It’s that it applies more to those companies, that those people value it more, and they’d be willing to pay for it more, or however you judge your value there. Clearly, small companies would value all this automation, and everything else, but they’re not going to get as much incremental value out of it, as a larger company would.

The other way to look at it is that this is pretty advanced stuff, and frankly,

it doesn’t deserve to be, free, open source. It’s probably really complicated

stuff, and you’re going to have to pay there. [Editor's note: Advancedness is not a criteria in open sourcing or not open sourcing. There are advanced features that are open source, such as Review Apps. There are basic features that are proprietary, such as File Locking. The criteria we use to decide which version the features go in are documented on our stewardship page.] Maybe there’d be levels to it,

right? There’d be a version that gives you an alert: we’ll run this test once a

day. Or even just have a blog post about how to do this: you set up a recurring,

scheduled pipeline job, once a day, to test if any of your dependencies have

been updated. And you can do that today and then it would alert you. But to

automate it, to actually, create a merge request for you, and everything else?

Well, that’s in the Enterprise feature. It’s not that version checking isn’t

important for everybody, but the automation around it really, really matters for

larger companies. Does that make sense?

Courtland: Yeah, I mean, I think that the first way you described it, in that, "Yeah, everyone gets some value out a feature like this, but the overwhelming value and use for this is in larger development teams," that resonated.

SLO and auto revert – #1661

This is a feature showing how we’re thinking about auto reverting something. We’ve got canary deployments, and we have another feature we’re not currently working on or scheduled, but it’s incremental rollout, so that you would not just rollout to a single canary, or a bucket of canaries, but it would slowly increment: 1 percent, then 5 percent, then 25 percent. But let’s say, at some point, during my rollout, you detect an error.

This a mockup of what it would look like. You’re like, "Oh, error rates increased by something above our threshold; let’s revert that one, go back, and create a new issue, and alert somebody to take a look at it." Lately, I’m thinking that I don’t know if I really want to automatically roll back, versus just stop it in its canary form, and say, "Well, it’s canary. Let’s let canary be there, so you can debug the canary, but just don’t let the canary go on further."

Error rate exceeding is a pretty tough one. But let’s say memory bumps up, and you might be like, "Yeah, we added something, and it’s using more memory, and we’re okay with that. Don’t stop my deploy just because it’s using more memory." There might need to be human intervention in there, but somewhere along this line we’re automating a lot of the deploy stuff.

Onboarding and adoption – #32638

Onboarding and adoption is a really big issue, with lots of different ideas for how to improve onboarding, how to get people actually using idea to production, improving auto deploy. Not a lot of visuals, so I won’t really talk about it, but it’s definitely one of our top priorities; the next most important thing we’re working on.

Cloud development – #32637

Cloud development is the idea that setting up your local host machine is actually kind of a pain sometimes. Especially with microservices, where each service can be in their own language, you don’t want to maintain Java, and Ruby, and Node, and all these other versions of dependencies, and every time something switches, you’ve got to reinstall a new version of stuff. Or even these days, you might develop on an iPad, and you don’t have a local host to compile things.

Cloud9 is the biggest, well known thing, from an IDE perspective, and Amazon bought them a little while ago. But even aside from the IDE portion of it, it’s just being able to develop in the cloud, and being able to make some changes, and then push them back; commit them to a repo.

We have a little bit of a demo like this, right now, with our web terminal. So, if you have Kubernetes, you see this terminal button, and it just pops up the terminal right in the staging server. And I can actually go ahead and edit a file there, and... I just made a live change into my staging app.

Now, generally speaking, I would not actually recommend you do that, because I’m messing with my staging app, that’s not what it's for. It makes an awesome little demo, but it’s not what you should do. What we want to do is come up with a way that people could do that, but have it be not on your staging app, but in maybe a dev environment that is specifically for this purpose. But that also, after you make your changes, and test them, and run them live, you can then go and commit them back to version control, and close that loop. So there’s a whole bunch of issues related to that. And to be honest, it was what we were hoping that Koding would have provided for us, and we have an integration with them, but it hasn’t worked out, really, the way that we had hoped. And so, we’re looking at alternatives, and we think we can probably do this ourselves.

Anyway, that’s a big thing to flesh out.

GitLab PaaS – #32820

Heroku is awesome, because it gives you this really great platform that’s easy to use, and gives you all this functionality on top of Amazon. Five or six years ago it was super, brain-meltingly awesome to get people to do ops. For a developer, I don’t have to be aware of how to do ops; Heroku just does ops for us.

GitLab PaaS is basically the idea that you’ve got a lot of these components, and we’re not going to invent them all from scratch. We’re going to rely on Kubernetes, for example. But on top of Kubernetes, we could make an awesome environment for ops. An ops environment, or a platform as a service. And so, there’s an issue to discuss what it would take to do that. At some point in time, this is a big item for us. If we can make it super really easy for you to fully manage your ops environment via GitLab, and maybe, for example, never touch the Kubernetes dashboard; never touch any of the tools, just use the GitLab tools to do this. That’s pretty powerful.

Sort of related is an idea in the onboarding stuff, that on GitLab.com we can actually provide you with a Kubernetes cluster; maybe a shared cluster. We have to worry about security, of course. But imagine if you were a brand new user on GitLab.com, and you push up an app, and you have nothing in there specifically for GitLab, you just push up your code, and GitLab is like, "Oh, that’s a Ruby app. Okay, I know how to build Ruby apps. Oh, and I also know how to test Ruby apps. I’m just going to go and test them automatically for you." And, "Oh, by the way, I know how to deploy this. I’m just going to go ahead and deploy this to production." And we’ll make a production.project-name.ephemeral-gitlabapps.com, whatever the hell, some domain so that it’s not going to affect your actual production. But if you wanted to, you would just point your DNS over to this production app, and you've got the production app running on GitLab infrastructure. And that’s, really, what Heroku provided, right?

But that also is an onboarding thing for us to make it really easy. Because if we want everybody to have CI, well, let’s turn it on for you. That’s pretty awesome. If we want everybody to have CD, we can’t just turn it on for you, because you have to have a place to deploy it to. So, if we just provided you a Kubernetes cluster ("everybody gets a cluster"), then you just got a place. And, I mean, we’ll severely limit it. We’ll make it limited in some way, so that you’re not going to run the production stuff for long there. Or if you do, you have to pay for it. But we’re not going to try and make money off of the production resources. We want to make money off of making it really easy. So, really, what we want to do is encourage you to, then, go and spin up your own Kubernetes cluster, say, on Google. And we’ll make a nice little link that says, "Go and spin up a cluster on GKE." We’ll make that really, really easy, but to make it super easy, for some number of days, we can just provide you that cluster, automatically.

Feature flags – #779

Feature flags are really about decoupling delivery from deployment. It’s the idea that you make your code, you deploy it, but you haven’t turned it on, so it’s not delivered yet. And the idea there is that it means you can merge in the main line, more often, because it’s not affecting anybody. And, also, it really helps because you can do things like: when I do deliver, I can deliver it for certain people; just GitLab employees or just the Beta group, and then I can control that rollout. So then, if there's an error rate spike, well, it’s just a few a people and I know who they are, and they’re going to complain to me. It’s no big deal. But I can test things out, get it polished, fix the problems, before rolling it out. And then, you can also do things like, roll it out to 10 percent of the people, 50 percent of the people, whatever. It’s all about reducing risk, and improving quality, and fundamentally about getting things into your mainline quicker. So, it’s ops-ish, in that sense, but it’s, really, still pretty fully on dev.

Artifact management – #2752

Artifact management has become a hot topic lately. We already have a container registry for Docker image artifacts, and we also have file-based artifacts that you can pass between jobs, and pass between pipelines, and even pass between cross project pipelines. And we have ways to download them, and browse them, but if those artifacts happen to be things like Maven or Ruby or node modules, and you want to publish them, and then consume them in other pipelines, we don’t have a formal way to do that.

And you could, obviously, publish to the open source, RubyGems, for example. But if you want a private Gem, that is only consumed by your team... Maybe that's not as big for Ruby developers, but Java developers do that all the time. A lot of Java developers use Artifactory or Sonatype Nexus. In order to complete the DevOps tool chain, we need to have some first class support for that, either by bundling in one of these other providers, or by adding layers, and APIs, on top of our existing artifacts. My personal pet favorite right now is, let’s say we can just tag our existing artifact, and say, "Oh, this is Maven type of artifact," and then we expose that via an API and so then you can declare that in another project, and it would just consume the APIs, and just know how to do that. But it would also use our built-in authentication so you don’t have to set up creds and do all this declaration; you can be like, "Oh, I’ve got access to this project and this project, so I can get the artifacts, and I can consume it all really easily."

Auto DevOps – #35712

Note: We shipped the first iteration of Auto DevOps in 10.0

So, let’s talk about Auto DevOps. This spans from the near-term to the very long-term. It’s great that we do a lot of DevOps, and in a very simplistic way, it’s like, "Oh, but shouldn’t we just make this stuff automatic?" The way I phrase it is, we should provide the best practices in an easy and default way. You can set up a GitLab CI YAML, but you have to actively go and do that. But, really, every project should be running some kind of CI. So, why don’t we just detect when you’ve pushed up a project; we’ll just build it, and we’ll go and test it, because we know how to do testing. Today, with Auto Deploy, we already use Auto Build, with build packs. We will automatically detect, I think, one of seven different languages, and automatically build your Java app, or Ruby, or Node... and we use Heroku’s build packs, actually, to do this build. And so we build that up, and when using Auto Deploy, we’ll go ahead and deploy that. You still have to, obviously, have a Kubernetes cluster in order to do that, so it’s not fully automated if you don’t have that. But if you’ve got Kubernetes, hey, this is a literally one click. You pick from a menu, say, "Oh, I’m on Kubernetes," and then hit submit, and you’ve got Auto Deploy and Auto Build.

But one of the things we don’t have is Auto CI. And that’s a little annoying, but it’s one of the things we want to pick up, and actually, hopefully our CTO, Dmitriy, is going to pick that up in Q3; it's one of his OKRs. Heroku, themselves, actually extended build packs to do testing, and so that means that there’s at least five build packs that know how to test these languages. And so, hey, let’s use that. But even if that doesn’t work, there’s a lot of other things we can do. Other companies have all this stuff automated, as well. So if we can’t use Heroku CI, being able to say, "Oh, this is this language; we know how to test this language," we'll be making that automatic.

Automatic is multiple levels of things. Is it a wizard that configures this stuff for me? Is it one click checkbox, that says, "Yes, turn on auto CI," or is it templates that I can easily add into my GitLab CI YAML? I think, in order to qualify as auto, what we have to do here is that it shouldn’t be templates. It shouldn’t be blog posts that tell me how to do it. That’s just CI. It should be, literally, just "I pushed and it worked;" or at most a checkbox or two.

Let’s go further, what other thing could we just automate here? And not automate strictly for the purposes of automation, but about bringing best practices to people. So, you have to actively work hard, to turn these things off. If you don’t want CI, then shut it off, but by default you should have this.

So, this is a really, really long list of things that will take us forever to get to. The first ones have links, because we’re tracking real issues for this. Auto Metrics is a great one. If you’re running certain languages, you should just be able to, really easily, go and just pull the right information out of there. But whatever, the list is huge.

But the idea is that we can build up this Auto DevOps, even the marketing term, and start talking about it in that way, and to not just say that GitLab is great for your DevOps and is a complete DevOps tool chain. But, in fact, we do all this stuff for you automatically.

There’s a lot to be done to make this fully automated. And what percentage of projects can we really do? Auto Deploy is a great example that only works for web apps. If it’s not a web app, we can’t just deploy it. What would it mean? We deploy it, and it just wouldn’t function. If you made a command line app, what would deploy even mean? Or if it’s a Maven, or really any kind of module that you bundled up and released, that’s not the same thing as a deploy. So, maybe we need an Auto Release. It’s not on this list, but maybe it should be. But within the web app space, we can do some of this stuff automatically.

So that’s it. Everything you ever wanted to know about DevOps.

We want to hear from you

Enjoyed reading this blog post or have questions or feedback? Share your thoughts by creating a new topic in the GitLab community forum.Share your feedbackFind out which plan works best for your team

Learn about pricingLearn about what GitLab can do for your team

Talk to an expert